TADA Weekly | Pre-Islamic Turkish History Series — Article 1

Kül Tigin stele, Orkhon Valley (Mongolia), ca. 732–735 CE. Photo © UNESCO World Heritage Centre / Orkhon Valley Cultural Landscape archives (https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1081/).

1 · Introduction

The study of pre-Islamic Turkic societies rests on a layered and uneven evidentiary base. The earliest written descriptions appear in Chinese dynastic annals compiled between the 2nd century BCE and the 10th century CE, notably the Shiji (Sima Qian, 91 BCE) and Hanshu (1st c. CE). These texts record organized steppe polities north of China, including the Xiongnu Confederation (209 BCE–93 CE) (Golden 1992, 15–23; Taşağıl 2013, 33–45).

Archaeology, however, pushes the cultural sequence further back. Researchers such as Semih Güneri (2020; 2021) and Mehmet Işıklı (2010) trace metallurgical, funerary, and symbolic continuities in the Altai–Sayan region into the second millennium BCE, linking Late Bronze and Early Iron Age horizons to the later Turkic world (Güneri 2020, 18–32; Işıklı 2010).

A Broader Steppe Continuum: From the İskit to the Xiongnu

İskit Material Culture

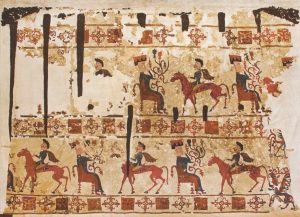

Pazırık kurgan artifacts, 5th–3rd centuries BCE, Altai Mountains. State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg (https://www.hermitagemuseum.org/).

Archaeological parallels connect İskit (Scythian) cultures (8th–3rd c. BCE) with later Turkic societies: horse-centered nomadism; kurgan burials with animal interments; composite bows; and animal-style art (Ögel 1984, 41–46; Tezcan 2012, 55–59). Radiocarbon-dated İskit kurgans at Arzhan and Pazırık (ca. 900–300 BCE) display these traits (Güneri 2020, 26–32). While İskit languages were likely Indo-Iranian, several historians argue that their ecological and symbolic repertoire fed into the Proto-Turkic horizon (Golden 1992, 17–19; Karatay 2003, 29–35).

Hence the chronological scope depends on evidence type:

-

Textual: begins in the 2nd c. BCE (Chinese annals).

-

Archaeological: extends to Karasuk–İskit–Tagar (ca. 1400–300 BCE).

-

Linguistic: places Proto-Turkic emergence in Altai–Sayan, ca. 1000–500 BCE (Erdal 2004; Karatay 2003; Johanson & Csató 1998).

This review follows both lines and indicates where written and material sources intersect or diverge.

On Identity and Definition

Terminology matters. Here “Turkic/Turkish” denotes a linguistic–cultural continuum, not a fixed ethnos. Early Chinese sources use varied exonyms (Hu, Xiongnu, Tujue) for heterogeneous steppe groups; the ethnonym “Türk” appears in both external and internal records only in the 6th–8th centuries CE (Zhoushu 636 CE; Orkhon inscriptions 716–735 CE) (Golden 1992, 27; Taşağıl 2013, 58). Archaeological and genetic studies (Güneri 2020; 2021; Jeong et al. 2020) indicate that populations later identified as “Turkic” emerged from a mosaic of older steppe cultures. A separate article in this series will examine Turkic ethnogenesis in depth.

2 · Textual and Linguistic Evidence

Orkhon Inscriptions Museum

Khöshöö Tsaidam Museum of the Orkhon Inscriptions, Arkhangai Province, Mongolia. Photo © UNESCO World Heritage Centre / Orkhon Valley Cultural Landscape archives.

2.1 Chinese Dynastic Sources (2nd c. BCE – 10th c. CE)

The Shiji and Hanshu detail Xiongnu political organization, dual east–west administration, and treaty relations (Golden 1992, 18; de la Vaissière 2005, 21–23). Later Zhoushu and Suishu (636 CE) identify the Göktürks (552–630 CE), their Altai iron base, and succession after the Rouran (Taşağıl 2013, 57–66). These annals are ideologically framed but provide chronological anchors that can be cross-checked against Turkic and Sogdian sources.

2.2 Runiform and Sogdian Sources (8th c. CE)

The Orkhon inscriptions—Tonyukuk (ca. 716 CE), Kül Tegin and Bilge Qağan (ca. 732–735 CE)—are the earliest self-authored Turkic texts. They confirm internal vocabulary (el, beg, toy) and cosmological terms (Tengri, Yer-Sub) (Erdal 2004, 112–130; Alyılmaz 2005, 77–86; Aydın 2019, 49–55). Dates and events align with Tang records (Sinor 1990, 132–134). Sogdian letters (ca. 700 CE) and Turfan documents (7–9 c. CE) show Turkic roles in Silk Road trade (de la Vaissière 2005, 89–94).

2.3 Linguistic Reconstruction (Proto-Turkic, ca. 1000–500 BCE)

Comparative linguistics places Proto-Turkic in Altai–Sayan by the early Iron Age; shared lexemes for metallurgy, horse gear, and kinship predate textual attestations (Erdal 2004, 22–25; Johanson & Csató 1998, 15–21). Karatay (2003, 43–52) integrates these with archaeology to argue a cultural–linguistic continuum from Karasuk/Tagar to early Turkic.

3 · Archaeological and Environmental Data

Archaeological site in the Altai region, Kazakhstan (2023). Photo credit: Professor Victor Mertz / The Astana Times. Source: “Archaeological Discoveries Unveil New Aspects of Turkic Heritage in Altai Region,” The Astana Times, November 2023 (https://astanatimes.com/2023/11/archaeological-discoveries-unveil-new-aspects-of-turkic-heritage-in-altai-region/).

Systematic work since the 1970s outlines material continuity from the Late Bronze Age into the early medieval period:

| Cultural Horizon | Dates | Core Region | Key Traits | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Karasuk | 1400–800 BCE | Minusinsk–Altai | Bronze metallurgy; horse harness | Güneri 2020; Işıklı 2010 |

| Tagar | 800–200 BCE | Minusinsk Basin | Large kurgans; animal-style art; iron tools | Tezcan 2012 |

| Xiongnu Sites | 3 BCE–1 CE | Mongolia & Ordos | Elite kurgans; Chinese imports | Böhmer 2020; de la Vaissière 2005 |

| Altai Metallurgy | 6th c. CE | Altai Mountains | Iron smelting noted in Zhoushu ch. 50 | Taşağıl 2013 |

Güneri’s “Türk-Altay Kuramı” integrates these layers into an Altai Cultural Complex across 2nd millennium BCE → 1st millennium CE, emphasizing technological and funerary continuities, supported by radiocarbon sequences (Güneri 2021, 59–68). Ancient DNA from Khövsgöl/Yenisei (3000 BCE–1300 CE) indicates admixture yet regional persistence (Jeong et al. 2020). Together, the data point to biocultural continuity rather than abrupt replacement.

4 · Political Organization and State Formation

A recurring steppe pattern moves from tribal confederation to centralized khaganate and back, conditioned by ecology and inter-polity competition (Honeychurch 2015, 52–60).

-

Rouran Khaganate (330–555 CE): formalized the title khagan (Wei shu, 554 CE).

-

Göktürk Khaganate I (552–630 CE): founded by Bumin in 552 CE after revolt; Altai core; dual east–west organization (Taşağıl 2013, 71–75).

-

Tang Interregnum (630–681 CE): Chinese domination; documented uprisings (Jiu Tang shu, 945 CE).

-

Göktürk Khaganate II (681–744 CE): restoration under Kutluk/Bilge; reforms dated 716–735 CE in Orkhon texts (Erdal 2004, 212–218).

Hereditary leadership was balanced by deliberative toy councils and tribute networks (Sinor 1990, 174–178; Durmuş 2010, 98–103).

5 · Religion, Ideology, and Cultural Thought

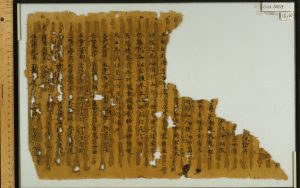

Image – Uighur Manichaean Manuscript (Digital Turfan Archive)

Uighur manuscript fragment (Uighur script, 8th–9th centuries CE). Digital Turfan Archive, Berlin State Library / Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences and Humanities (BBAW). Source: https://turfan.bbaw.de/dta/ch_u/dta_chu0001.html.

5.1 Tengri Cosmology (6–8 c. CE)

The Orkhon corpus (716–735 CE) invokes Tengri as a cosmic ordering principle legitimizing rule; Yer-Sub (earth/water) and El (polity) express ecological–political balance (Róna-Tas 1999, 112–114). Ögel (1984, 59–63) reads this as a continuation of older steppe cosmology.

5.2 Religious Interaction (7–10 c. CE)

Manichaeism was adopted in 762 CE under Bögü Khagan; Turfan manuscripts (8–9 c.) preserve liturgy (Clark & Zieme 2012, 22–27). Islamization of Karluks/Karakhanids by ca. 960 CE altered ideology but preserved Turkic administrative lexicon (Golden 1992, 225–231; Taşağıl 2013, 122–126).

5.3 Mythology and Cultural Concepts

Turkish scholarship highlights mythic continuity underlying political ideals. Ögel (1971–72; 1984) and Türkmen (2011) analyze motifs—celestial wolf, mountain origin, light birth—persisting from Bronze/Iron Age horizons into the Uighur era. Durmuş (2009, 145–150) connects these to leadership ethics; their presence in 8th-century inscriptions suggests cultural, not merely confessional, continuity.

6 · Continuity and Transformation (9–11 c. CE)

After the Uighur collapse (840 CE), the Kyrgyz dominated the Yenisei (9th c.), while Karluk groups moved west. The Karakhanid State (940–1040 CE) represents the first Islamic Turkic polity; institutional survivals include titles (bey), legal instruments (yarlıq), and tamga traditions (Taşağıl 2013, 133–138; Durmuş 2010, 117–121).

7 · Conclusion

Two complementary chronologies emerge:

-

Textual chronology (from the 2nd c. BCE): establishes named entities and events (Chinese annals; Orkhon inscriptions).

-

Archaeological–linguistic chronology (from ca. 1400 BCE): shows long-term Altai–Sayan continuity (Karasuk/Tagar → İskit/Scythian horizons → early Turkic), reinforced by archaeogenetics.

Together they support a model of gradual, regionally grounded evolution rather than sudden ethnogenesis.

Chronological Appendix — Major Cultural Horizons and Polities

| Horizon / Polity | Dates | Region | Defining Features | Primary Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Karasuk Culture | 1400–800 BCE | Minusinsk–Altai | Bronze metallurgy; horse gear | Archaeology (Güneri 2020; Işıklı 2010) |

| Tagar Culture | 800–200 BCE | Minusinsk Basin | Iron tools; animal-style art | Archaeology (Tezcan 2012) |

| İskit/Scythian Kurgans | 900–300 BCE | Altai, Tuva, Pontic steppes | Kurgans; animal art; horse sacrifice | Hermitage coll.; Güneri 2020 |

| Xiongnu Confederation | 209 BCE–93 CE | Mongolia & Ordos | Dual polity; treaties | Shiji; Hanshu |

| Rouran Khaganate | 330–555 CE | Mongolia & Altai | Title khagan | Wei shu; Zhoushu |

| Göktürk Khaganate I | 552–630 CE | Altai–Central Asia | First state using ethnonym “Türk”; iron base | Zhoushu; Suishu |

| Tang Interregnum | 630–681 CE | Mongolia | Chinese domination; revolts | Jiu Tang shu |

| Göktürk Khaganate II | 681–744 CE | Orkhon Valley | Restoration; reforms 716–735 CE | Orkhon inscriptions |

| Uighur Khaganate | 744–840 CE | Mongolia & Turfan | Manichaeism 762 CE; literate bureaucracy | Turfan texts; Chinese records |

| Kyrgyz Dominance | 840–950 CE | Yenisei | Post-Uighur rule | Arabic–Persian geographies |

| Karakhanid State | 940–1040 CE | Transoxiana | First Islamic Turkic polity | Hudud al-ʿĀlam; Kashgari |

References (Chicago Author–Date; Turkish entries bilingual)

Alyılmaz, Cengiz. 2005. Orhon Yazıtları: Dönemi, Coğrafyası, Yazısı, Dili ve Anlam Dünyası [The Orkhon Inscriptions: Period, Geography, Script, Language, and World of Meaning]. Ankara: Türk Dil Kurumu.

Aydın, Erhan. 2019. Türk Runik Yazıtları [Turkish Runic Inscriptions]. Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu.

Beckwith, Christopher I. 2009. Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Böhmer, Anna. 2020. “Climate and Mobility on the Eurasian Steppe: A Paleoenvironmental Synthesis.” Quaternary International 556: 12–27.

Clark, Larry V., and Peter Zieme. 2012. Manichaean Texts from the Uighur Kingdom of Turfan. Turnhout: Brepols.

de la Vaissière, Étienne. 2005. Sogdian Traders: A History. Leiden: Brill.

Durmuş, İlhami. 2009. Türklerin Tarihi ve Kültürü [History and Culture of the Turks]. Ankara: Grafiker.

Durmuş, İlhami. 2010. Orta Asya Türk Tarihi ve Uygarlığı [Central Asian Turkish History and Civilization]. Ankara: Pegem Akademi.

Erdal, Marcel. 2004. A Grammar of Old Turkic. Leiden: Brill.

Golden, Peter B. 1992. An Introduction to the History of the Turkic Peoples. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

Güneri, Semih. 2020. Türk-Altay Kuramı ve Arkeolojik Bulgular I: Altay Kültür Kompleksi Üzerine Yeni Değerlendirmeler [The Turkic-Altai Theory and Archaeological Findings I]. Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu.

Güneri, Semih. 2021. Türk-Altay Kuramı ve Arkeolojik Bulgular II: Erken Türk Arkeolojisinin Doğu ve Batı Altay Boyutları [The Turkic-Altai Theory and Archaeological Findings II]. Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu.

Honeychurch, William. 2015. Inner Asia and the Spatial Politics of Empire. New York: Springer.

Işıklı, Mehmet. 2010. Doğu Anadolu Erken Demir Çağ Kültürleri ve Transkafkasya İlişkileri [Eastern Anatolian Early Iron Age Cultures and Transcaucasian Relations]. Erzurum: Atatürk Üniversitesi.

Jeong, Choongwon, et al. 2020. “A Dynamic 6,000-Year Genetic History of Eurasia’s Eastern Steppe.” Cell 183 (4): 890–904.

Johanson, Lars, and Éva Á. Csató, eds. 1998. The Turkic Languages. London: Routledge.

Karatay, Osman. 2003. Türklerin Kökeni [The Origins of the Turks]. Ankara: Karam.

Karatay, Osman. 2006. İran ve Turan: Eskiçağ’da Doğu-Batı Mücadelesi [Iran and Turan: East–West Struggle in Antiquity]. Ankara: Karam.

Ögel, Bahaeddin. 1971–72. Türk Mitolojisi I–II [Turkish Mythology I–II]. Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu.

Ögel, Bahaeddin. 1984. İslamiyet’ten Önce Türk Kültür Tarihi [Pre-Islamic Turkish Cultural History]. Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu.

Róna-Tas, András. 1999. Hungarians and Europe in the Early Middle Ages. Budapest: Central European University Press.

Sinor, Denis, ed. 1990. The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Taşağıl, Ahmet. 2013. Kök Tengri’nin Çocukları: Avrasya Bozkırlarında İslam Öncesi Türk Tarihi [Children of Kök Tengri: Pre-Islamic Turkish History in the Eurasian Steppes]. Istanbul: Bilge Kültür Sanat.

Tezcan, Mehmet. 2012. Türk Kültür Tarihi: Erken Dönem [History of Turkish Culture: Early Period]. Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu.

Türkmen, Fikret. 2011. Türk Kültürünün Temelleri [Foundations of Turkish Culture]. İzmir: Akademi Kitabevi.

Image Rights & Attribution Sheet

| # | Institution / Source | Contact / Permissions Email | Relevant Collection / Object | Licensing / Rights Info | Suggested Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | UNESCO – Orkhon Valley Cultural Landscape (Mongolia) | wh-info@unesco.org; cc: wh-promotion@unesco.org | Site 1081 (includes Kül Tigin & Bilge Kağan steles) | Educational/non-commercial with credit; written permission for derivatives | “Kül Tigin stele, Orkhon Valley (Mongolia), ca. 732–735 CE. Photo © UNESCO World Heritage Centre / Orkhon Valley Cultural Landscape archives.” |

| 2 | Khöshöö Tsaidam Museum of the Orkhon Inscriptions | via Ministry of Culture, Mongolia: info@moc.gov.mn | Museum of the Orkhon Inscriptions (opened 2008) | Permission via Cultural Heritage Dept. | “Khöshöö Tsaidam Museum of the Orkhon Inscriptions, Arkhangai Province, Mongolia. Courtesy of the Ministry of Culture of Mongolia.” |

| 3 | State Hermitage Museum (St. Petersburg) | photo@hermitage.ru; press@hermitage.ru | Scythian Gold / Pazırık–Arzhan finds | Controlled license; scholarly use with credit + catalog ID | “Pazırık kurgan artifacts, 5th–3rd centuries BCE, Altai Mountains. State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg.” |

| 4 | Türk Tarih Kurumu (TTK), Ankara | ttk@ttk.gov.tr | Altay-Sayan field archives | Photo archive access on written request; academic credit required | “Altai–Sayan excavation overview. Courtesy of Türk Tarih Kurumu (Ankara) Field Archaeology Archive.” |

| 5 | Berlin State Library – Turfan Collection | turfanforschung@sbb.spk-berlin.de | Uighur/Manichaean/Buddhist manuscripts | CC BY-NC 4.0 for most digitized images | “Manichaean manuscript fragment (Uighur script, 8th–9th centuries CE). Turfan Collection, Berlin State Library.” |

| 6 | Kyrgyz National Museum of History (Bishkek) | museum@culture.gov.kg; info@nationalmuseum.kg | Karakhanid tomb tower inscriptions, Uzgen (11th c.) | Written permission required; usually grants academic use | “Karakhanid tomb tower inscription, Uzgen (11th century CE). Kyrgyz National Museum of History, Bishkek.” |

| 7 | National Museum of Mongolia (Ulaanbaatar) | info@nationalmuseum.mn | Bronze–Iron Age and Turkic artifacts | Often public domain for educational use with credit |